Report on the meeting on 26th October 2015

The Prior Rick Hudson welcomed members, including some new members. He then introduced Dr. Robb Robinson. He is from a seafaring family and lectures at Hull University. His particular interest is maritime history. His illustrated talk was entitled, “Dynamic Energetic Coast, the East Riding, its People, and the Sea” and concentrated on the Holderness coast. The research behind this talk was sponsored by a number of groups including the Holderness Fisheries Local Action Group. Throughout the talk Robb interspersed some local characters, from admirals to pirates.

Robb explained how Holderness looked in the distant past. The Humber estuary would at times have been much wider and Holderness itself would have been pockmarked by Meres which were a valuable resource providing fish and reeds. Some villagers even paid their rent in eels. But because the geology is juvenile, laid down only in the last ice age, the coast is fast eroding. In 1799 Owthorne church had to be demolished and rebuilt further inland. In 1826 Kilnsea church fell into the sea, the last service there being just the Sunday before.

Ravenser Odd at Spurn point, washed away by the sea in the 1300’s was a large town which derived its wealth from fishing, and Robb explained that fishing is the oldest economic activity in this area. The 2600 year old carved figures from Roos Carr are standing in a boat. In the 1700’s many large Dutch vessels called Busses drifted for herring and often beached on the coast. Robb showed a press report from the early 1800’s complaining of an “invasion” by 700 Dutch fishermen who demanded food from the locals. Large trawl nets were experimented with out of Bridlington in around 1820 but not taken up locally until later.

Excavating gravel and stones from beaches and offshore banks was widespread in the 1800’s. The first Westminster Bridge was built of cobbles from the Holderness coast, and many local churches are too.

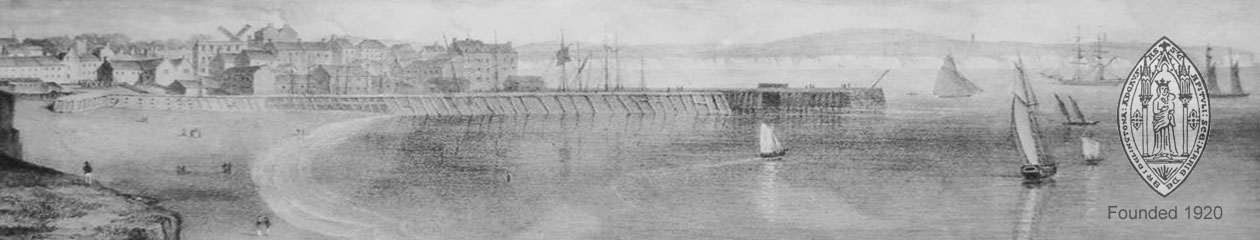

Robb considered why the harbour at Bridlington when newly extended in the 1850’s was so large. Trade alone did not warrant such a size. The answer is that Bridlington harbour was a “Port of Refuge” and gained a lot of income from passing tolls. Before the railways, the seaways of the east coast were like the M1, and traffic routes from Scandinavia heading for the Flamborough Head landmark could be likened to the M18. Bridlington then was in a good position to be a service station, and made money from provisioning, harbouring and repairing passing vessels.

In recent years local boats have switched to shellfish. Fishing at Bridlington is booming while elsewhere fishing fleets are in decline. Years ago oats were shipped from Bridlington to London to feed the capital’s horses, an early green fuel. Today, in the sea off Holderness, windfarms are being built among the existing gas platforms. Robb concluded that the story of the Holderness coast remains a vibrant one.

The vote of thanks was given by Judy Wilson. She was impressed by his breadth of knowledge, and thought the words dynamic and energetic could also be applied to the presentation itself.